In the book Visual Usability, we introduce what we call the "meta-principles" – three principles that are fundamental to the success of user interfaces. Consistency, hierarchy, and personality are not new to UI design. Considered primarily, however, they provide a structure for assessing and making decisions about the large and small visual characteristics of a UI design. When designing, keeping these principles in mind helps focus thinking about the effect of visual characteristics on how people interpret what they see from both the functional and aesthetic standpoints.

Interfaces have a big job to do. They need to provide information on multiple levels – convey content, communicate interactivity, and provide feedback. Before they can do that, they need to help someone know, or reinforce expectations of, what they are looking at. In Visual Usability, we go into detail about how visual characteristics of layout, type, color, imagery, and controls affect perception of consistency. Our goal is to raise awareness of these details and their effects. We want to help teams understand how people perceive visual characteristics, and make conscious decisions about them.

This post begins to address consistency in the big picture – as a principle for considering the approach to an interface rather than its details – concepts on a different strategic plane than where to place a button. From this perspective, it helps frame thinking about UX, and align UX with how it is represented through UI.

Internal consistency

Humans are wired to identify patterns in what we see and assign meaning to them. When establishing consistency within an application, lack of attention to consistent placement, color, styling, imagery (including symbols and icons), and typography can indicate difference to users, breaking the patterns they've perceived, and making them "stop and think."

This version of an older application had three separate ways of closing a window, forcing users to remember different paradigms every time they interacted with it.

Making sure a UI is internally consistent – that all the close buttons are styled similarly and placed similarly within a screen and from screen to screen within an application, for example – is familiar territory. Making sure that the patterns you choose to adopt and make consistent are in line with your users’ expectations is also familiar territory. What is different is calling out and thinking about the role consistency plays in affecting perception at the UI framework level.

External consistency

When Google created and launched Google Docs, the interface adopted symbols and patterns familiar to people who use desktop word-processing programs. This was a smart move strategically; consistent symbols reinforced similarities between the desktop and cloud word processing experiences, making Google Docs seem familiar and approachable. This helped Google transition users to word processing in the cloud. Consistency across platforms or applications is external consistency.

Google Docs UI, top; Microsoft Word 2010, bottom.

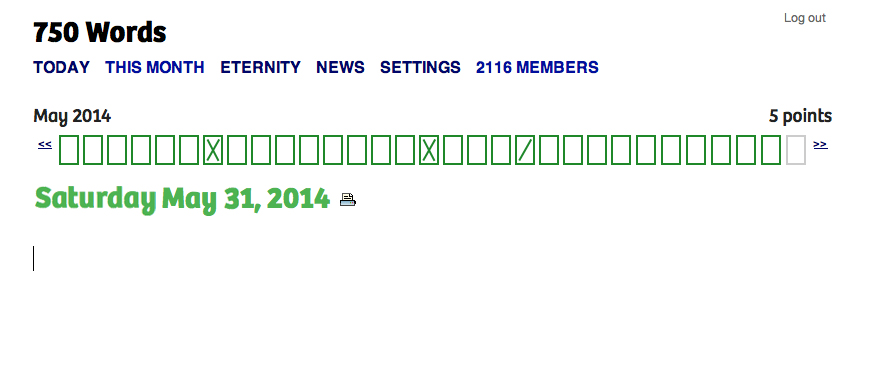

750words.com is also an application used for writing, but it has a different goal, and targets different users. Its tag line is "Private, unfiltered, spontaneous, daily," and the site focuses on people who want to write regularly. The UI provides only essential visual information – where to type – and the number of words written. The screen shows optional visual feedback for how often people are writing. UI elements and design characteristics do not say "word processing," but still encourage people to write. The decision to design the UI framework to be inconsistent with word processing applications helps the app show how it is different from – and better suited to – helping people write regularly.

750words.com only indicates where to write, and supports writing regularly.

Consistency and novelty

Advertising and promotional media in general rely on inconsistency – or novelty, as it's known in communication theory – to get people's attention. Novelty can be a differentiator. Novelty as an approach can succeed when it’s authentic and effectively represents and reflects a difference that people find valuable. 750words.com takes a novel approach to writing online, and the choices made in its interface reflect that. Novelty can make visual information more memorable, as several studies,including this October 2013 one [PDF], have found.

While there’s nothing wrong with using platform standards as the initial foundation for a design, relying on them for the final design inevitably results in an app that lacks unique visual appeal. An app designed this way may get to market more quickly than an app that doesn’t, and provides interface characteristics consistent with other apps, rendering it easy to pick up and use. But without key visual differentiators that distinguish it from its competitors and help audiences build affinity, it risks falling behind the pack by not standing out.

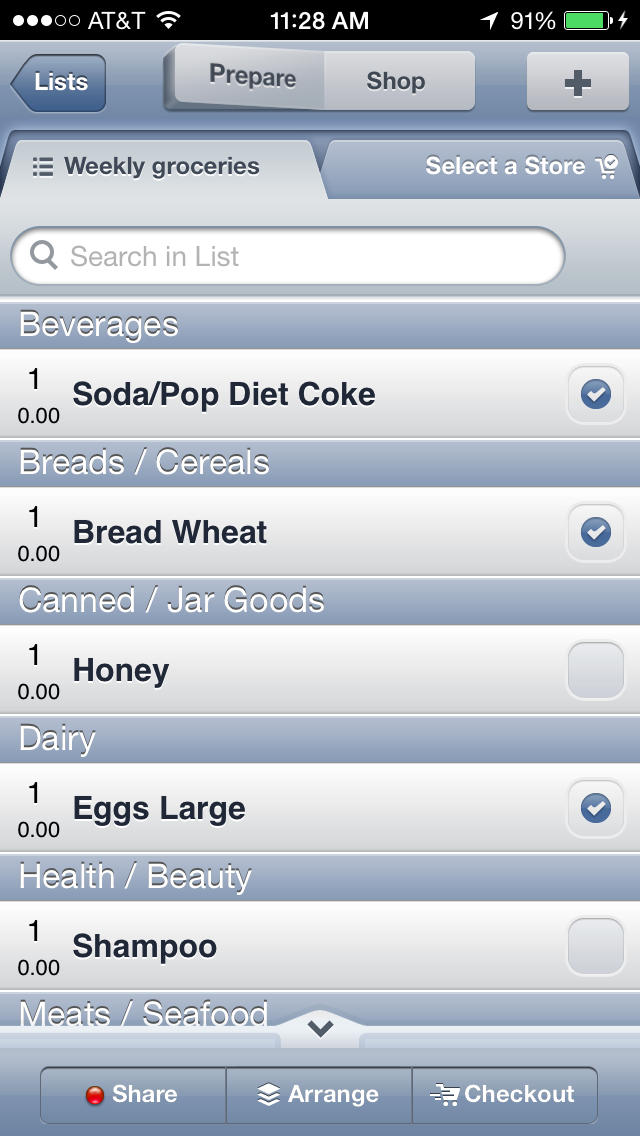

For example, compare OpenMBTA (below left), an app for Boston’s public transportation system, to Grocery Gadget (below right), a grocery shopping app:

The apps serve completely different purposes, but because both rely almost entirely on iOS 6 visual conventions, they look so similar that they might as well be the same app. Even the custom “prepare/shop” toggle at the top of the Grocery Gadget screen isn’t enough to visually distinguish it from OpenMBTA.

By contrast, public transportation app CG Transit, while basing some of its look and feel on iOS 7 flat design standards, applies simple visual upgrades that push it beyond the base set of rules. Color bullet points connect a list of stops, a gradated map gives a high-level overview of the subway line’s path through the city, and a side menu with icons and color highlights combine to create classic visual appeal that make CG Transit feel fresher and friendlier than OpenMBTA.

Striking a balance between consistency and novelty is at the heart of designing an effective and desirable user experience and interface. As one of the key visual principles behind what people notice and why, we hope you'll reconsider consistency, be aware of it, and use it when making decisions about how to approach and design visual interfaces.

Deborah A. Levinson also contributed to writing this blog post.